Although a handful of scientific studies have compared the effectiveness of some of the filters out there, the results vary based on methodology and variables like washing-machine model, fabric type, and detergent. To make things more complicated, there’s not yet a standardized, peer-reviewed metric or certification for comparing the claims of these filters, as there is for, say, water filters. Also, there isn’t a lot of competition for microfiber filters, especially for ones available in the United States. For now, we can’t give authoritative advice about which of these options is the “best.” There are many factors affecting the performance of these filters, such as washing-machine type, the size and makeup of a laundry load, the detergent, and the wash cycle. I ordered a few of these filters to view them firsthand, and I’ve used a couple of them in recent weeks. Though these products won’t singlehandedly solve the massive global problem of microplastic pollution, they may raise awareness and help reduce wastewater pollution on an individual scale. Girlfriend Collective-which makes one of our leggings picks from recycled polyester sourced partially from recycled PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottles-now sells a microplastics filter that you attach to your washing machine (albeit with some difficulty, according to reviews). The Guppyfriend laundry bag and the Cora Ball are two of the better-known options. To address the microfiber pollution problem, a few products have cropped up that claim to keep microplastics out of wastewater when you wash your clothes. It’s all of these microplastics that you can’t see with the naked eye that are pervasive in the environment.” It’s not just plastic bags and soda bottles. “The face of that crisis looks a lot different. “We have a plastic pollution crisis,” said Alexis Jackson, a marine biologist and scientist with the California chapter of the Nature Conservancy, an environmental advocacy organization. That’s about 2.2 million tons of microfibers entering the ocean every year.

Today scientists estimate that textiles produce 35% of the microplastic pollution in the world’s oceans (in the form of synthetic microfibers), which would make textiles the largest known source of marine microplastic pollution. Specifically, the study found plastic microfibers-tiny polyester and acrylic threads that matched those in textiles. Just 10 years ago, a group of scientists published a breakthrough study of shorelines on six continents it pointed to laundry as a significant source of plastic pollution in the world’s oceans. The study of microfiber pollution is relatively new. These microfibers, which are stripped and carried off by friction and turbulence in the washing machine, enter our wastewater, eventually ending up in the environment. We now know that clothing, bedding, and other textiles shed microplastics in fiber form and (along with tire degradation and road runoff) are major contributors to global plastic pollution.

The human world runs on plastic, and microplastics come from a variety of sources: larger pieces of plastic (like bottles) that break apart into smaller and smaller fragments, car tires, plastic beads (including those in skin-care products), and synthetic fibers.

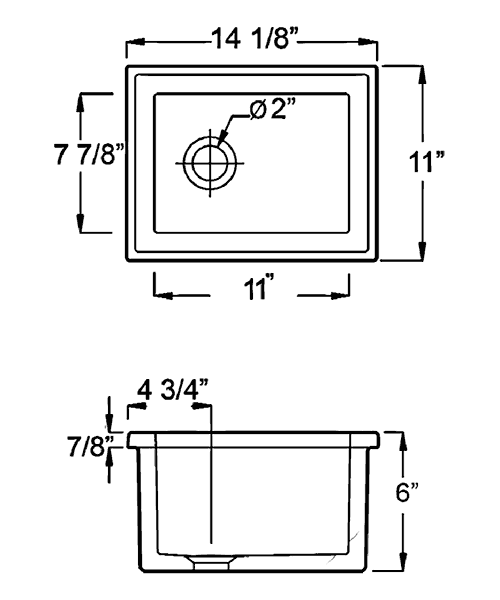

#Laundry sink size full

Or, as The New York Times reported: “18 to 24 shopping bags full of small plastic fragments for every foot of coastline on every continent except Antarctica.”

In October 2020, scientists in Australia published a study estimating that 9.25 to 15.86 million tons of microplastics can be found on the ocean floor. There is almost nowhere on earth that plastics haven’t been found, not even in the depths of the ocean. Microplastics are ubiquitous now-at the Jersey Shore of my childhood, in Hawaii and Japan (where my families live), and in California, my new home. These tiny pieces are called microplastics, and they measure less than 5 millimeters (PDF) in length (or, smaller than the width of a #2 pencil). So much of it is too tiny to hold or even see. I try to collect the shards, the bits of aquas, whites, and teals, but soon I give up, angry and defeated. Though often my feet find sharp things in the soft sand-not just gravel and pebbles but also, increasingly and overwhelmingly, plastic. I love to dig my toes into the suctioning sand and feel the swirl of a receding wave. My happy place is that chaotic zone of salt and spray where the beach meets the sea, a place of coming and going, flux and exchange.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)